UBUNTU: Installing LAMP Stack

Step 1 — Installing Apache and Updating the Firewall

The Apache web server is among the most popular web servers in the world. It’s well-documented and has been in wide use for much of the history of the web, which makes it a great default choice for hosting a website.

Install Apache using Ubuntu’s package manager, apt:

sudo apt update

sudo apt install apache2 -ySince this is a sudo command, these operations are executed with root privileges. It will ask you for your regular user’s password to verify your intentions.

Once you’ve entered your password, apt will tell you which packages it plans to install and how much extra disk space they’ll take up. Press Y and hit ENTER to continue, and the installation will proceed.

Adjust the Firewall to Allow Web Traffic

Next, assuming that you have followed the initial server setup instructions and enabled the UFW firewall, make sure that your firewall allows HTTP and HTTPS traffic. You can check that UFW has an application profile for Apache like so:

sudo ufw app listOutputAvailable applications:

Apache

Apache Full

Apache Secure

OpenSSHIf you look at the Apache Full profile, it should show that it enables traffic to ports 80 and 443:

sudo ufw app info "Apache Full"OutputProfile: Apache Full

Title: Web Server (HTTP,HTTPS)

Description: Apache v2 is the next generation of the omnipresent Apache web

server.

Ports:

80,443/tcpAllow incoming HTTP and HTTPS traffic for this profile:

You can do a spot check right away to verify that everything went as planned by visiting your server’s public IP address in your web browser (see the note under the next heading to find out what your public IP address is if you do not have this information already):

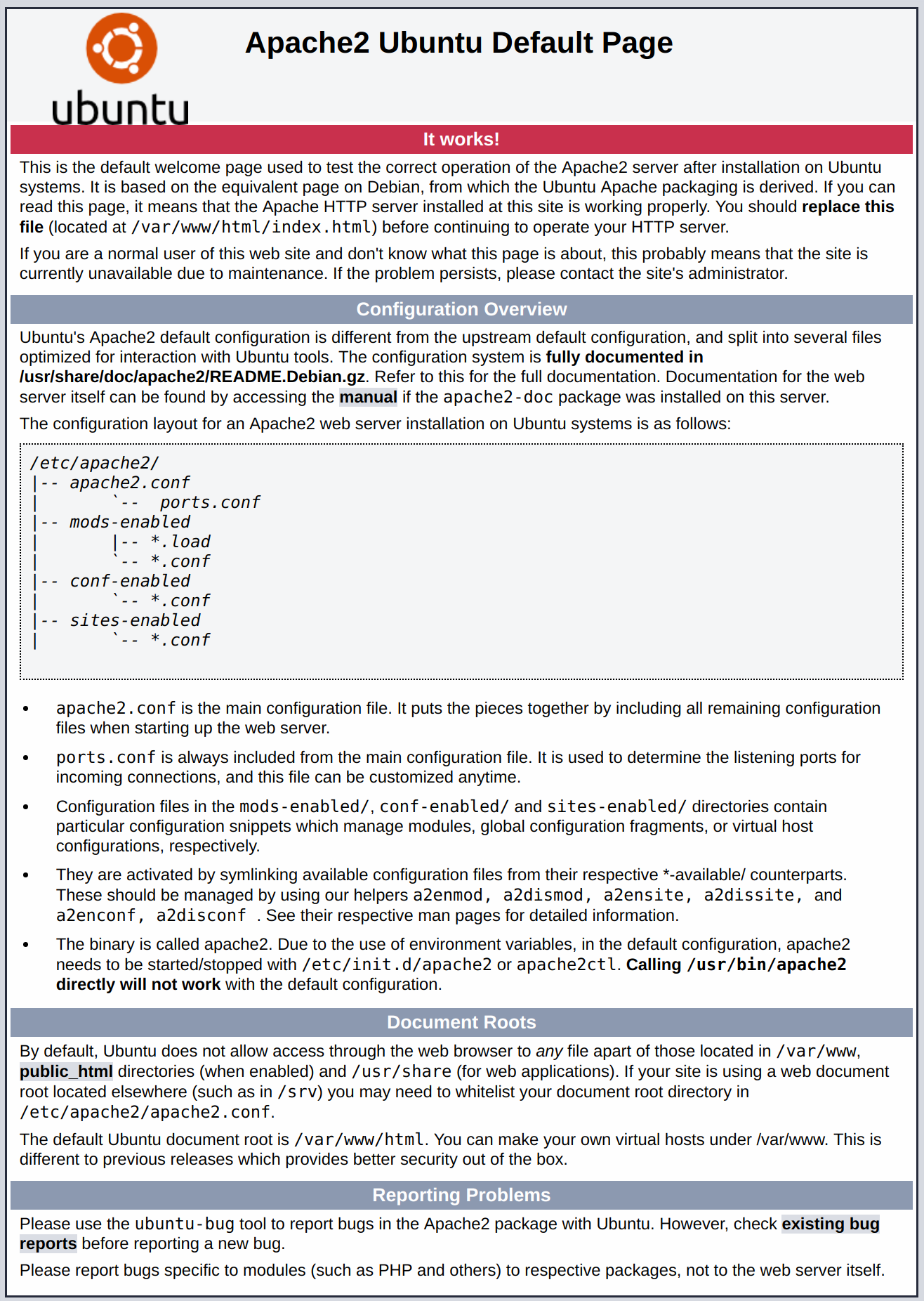

You will see the default Ubuntu 18.04 Apache web page, which is there for informational and testing purposes. It should look something like this:

If you see this page, then your web server is now correctly installed and accessible through your firewall.

How To Find your Server’s Public IP Address

If you do not know what your server’s public IP address is, there are a number of ways you can find it. Usually, this is the address you use to connect to your server through SSH.

There are a few different ways to do this from the command line. First, you could use the iproute2 tools to get your IP address by typing this:

This will give you two or three lines back. They are all correct addresses, but your computer may only be able to use one of them, so feel free to try each one.

An alternative method is to use the curl utility to contact an outside party to tell you how it sees your server. This is done by asking a specific server what your IP address is:

Regardless of the method you use to get your IP address, type it into your web browser’s address bar to view the default Apache page.

Step 2 — Installing MySQL

Now that you have your web server up and running, it is time to install MySQL. MySQL is a database management system. Basically, it will organize and provide access to databases where your site can store information.

Again, use apt to acquire and install this software:

Note: In this case, you do not have to run sudo apt update prior to the command. This is because you recently ran it in the commands above to install Apache. The package index on your computer should already be up-to-date.

This command, too, will show you a list of the packages that will be installed, along with the amount of disk space they’ll take up. Enter Y to continue.

When the installation is complete, run a simple security script that comes pre-installed with MySQL which will remove some dangerous defaults and lock down access to your database system. Start the interactive script by running:

This will ask if you want to configure the VALIDATE PASSWORD PLUGIN.

Note: Enabling this feature is something of a judgment call. If enabled, passwords which don’t match the specified criteria will be rejected by MySQL with an error. This will cause issues if you use a weak password in conjunction with software which automatically configures MySQL user credentials, such as the Ubuntu packages for phpMyAdmin. It is safe to leave validation disabled, but you should always use strong, unique passwords for database credentials.

Answer Y for yes, or anything else to continue without enabling.

If you answer “yes”, you’ll be asked to select a level of password validation. Keep in mind that if you enter 2 for the strongest level, you will receive errors when attempting to set any password which does not contain numbers, upper and lowercase letters, and special characters, or which is based on common dictionary words.

Regardless of whether you chose to set up the VALIDATE PASSWORD PLUGIN, your server will next ask you to select and confirm a password for the MySQL root user. This is an administrative account in MySQL that has increased privileges. Think of it as being similar to the root account for the server itself (although the one you are configuring now is a MySQL-specific account). Make sure this is a strong, unique password, and do not leave it blank.

If you enabled password validation, you’ll be shown the password strength for the root password you just entered and your server will ask if you want to change that password. If you are happy with your current password, enter N for “no” at the prompt:

For the rest of the questions, press Y and hit the ENTER key at each prompt. This will remove some anonymous users and the test database, disable remote root logins, and load these new rules so that MySQL immediately respects the changes you have made.

Note that in Ubuntu systems running MySQL 5.7 (and later versions), the root MySQL user is set to authenticate using the auth_socket plugin by default rather than with a password. This allows for some greater security and usability in many cases, but it can also complicate things when you need to allow an external program (e.g., phpMyAdmin) to access the user.

If you prefer to use a password when connecting to MySQL as root, you will need to switch its authentication method from auth_socket to mysql_native_password. To do this, open up the MySQL prompt from your terminal:

Next, check which authentication method each of your MySQL user accounts use with the following command:

In this example, you can see that the root user does in fact authenticate using the auth_socket plugin. To configure the root account to authenticate with a password, run the following ALTER USER command. Be sure to change password to a strong password of your choosing:

Then, run FLUSH PRIVILEGES which tells the server to reload the grant tables and put your new changes into effect:

Check the authentication methods employed by each of your users again to confirm that root no longer authenticates using the auth_socket plugin:

You can see in this example output that the root MySQL user now authenticates using a password. Once you confirm this on your own server, you can exit the MySQL shell:

At this point, your database system is now set up and you can move on to installing PHP, the final component of the LAMP stack.

Step 3 — Installing PHP

PHP is the component of your setup that will process code to display dynamic content. It can run scripts, connect to your MySQL databases to get information, and hand the processed content over to your web server to display.

Once again, leverage the apt system to install PHP. In addition, include some helper packages this time so that PHP code can run under the Apache server and talk to your MySQL database:

This should install PHP without any problems. We’ll test this in a moment.

In most cases, you will want to modify the way that Apache serves files when a directory is requested. Currently, if a user requests a directory from the server, Apache will first look for a file called index.html. We want to tell the web server to prefer PHP files over others, so make Apache look for an index.php file first.

To do this, type this command to open the dir.conf file in a text editor with root privileges:

It will look like this:/etc/apache2/mods-enabled/dir.conf

Move the PHP index file (highlighted above) to the first position after the DirectoryIndex specification, like this:/etc/apache2/mods-enabled/dir.conf

When you are finished, save and close the file by pressing CTRL+X. Confirm the save by typing Y and then hit ENTER to verify the file save location.

After this, restart the Apache web server in order for your changes to be recognized. Do this by typing this:

You can also check on the status of the apache2 service using systemctl:

Press Q to exit this status output.

To enhance the functionality of PHP, you have the option to install some additional modules. To see the available options for PHP modules and libraries, pipe the results of apt search into less, a pager which lets you scroll through the output of other commands:

Use the arrow keys to scroll up and down, and press Q to quit.

The results are all optional components that you can install. It will give you a short description for each:

To learn more about what each module does, you could search the internet for more information about them. Alternatively, look at the long description of the package by typing:

There will be a lot of output, with one field called Description which will have a longer explanation of the functionality that the module provides.

For example, to find out what the php-cli module does, you could type this:

Along with a large amount of other information, you’ll find something that looks like this:

If, after researching, you decide you would like to install a package, you can do so by using the apt install command like you have been doing for the other software.

If you decided that php-cli is something that you need, you could type:

If you want to install more than one module, you can do that by listing each one, separated by a space, following the apt install command, like this:

At this point, your LAMP stack is installed and configured. Before you do anything else, we recommend that you set up an Apache virtual host where you can store your server’s configuration details.

use this for setup your own Cloud VM for FREE ($100 credit)

Step 4 — Setting Up Virtual Hosts (Recommended)

When using the Apache web server, you can use virtual hosts (similar to server blocks in Nginx) to encapsulate configuration details and host more than one domain from a single server. We will set up a domain called your_domain, but you should replace this with your own domain name.

Apache on Ubuntu 18.04 has one server block enabled by default that is configured to serve documents from the /var/www/html directory. While this works well for a single site, it can become unwieldy if you are hosting multiple sites. Instead of modifying /var/www/html, let’s create a directory structure within /var/www for our your_domain site, leaving /var/www/html in place as the default directory to be served if a client request doesn’t match any other sites.

Create the directory for your_domain as follows:

Next, assign ownership of the directory with the $USER environment variable:

The permissions of your web roots should be correct if you haven’t modified your unmask value, but you can make sure by typing:

Next, create a sample index.html page using nano or your favorite editor:

Inside, add the following sample HTML:/var/www/your_domain/index.html

Save and close the file when you are finished.

In order for Apache to serve this content, it’s necessary to create a virtual host file with the correct directives. Instead of modifying the default configuration file located at /etc/apache2/sites-available/000-default.conf directly, let’s make a new one at /etc/apache2/sites-available/your_domain.conf:

Paste in the following configuration block, which is similar to the default, but updated for our new directory and domain name:/etc/apache2/sites-available/your_domain.conf

Notice that we’ve updated the DocumentRoot to our new directory and ServerAdmin to an email that the your_domain site administrator can access. We’ve also added two directives: ServerName, which establishes the base domain that should match for this virtual host definition, and ServerAlias, which defines further names that should match as if they were the base name.

Save and close the file when you are finished.

Let’s enable the file with the a2ensite tool:

Disable the default site defined in 000-default.conf:

Next, let’s test for configuration errors:

You should see the following output:

Restart Apache to implement your changes:

Apache should now be serving your domain name. You can test this by navigating to http://your_domain, where you should see something like this:

With that, you virtual host is fully set up. Before making any more changes or deploying an application, though, it would be helpful to proactively test out your PHP configuration in case there are any issues that should be addressed.

Step 5 — Testing PHP Processing on your Web Server

In order to test that your system is configured properly for PHP, create a very basic PHP script called info.php. In order for Apache to find this file and serve it correctly, it must be saved to your web root directory.

Create the file at the web root you created in the previous step by running:

This will open a blank file. Add the following text, which is valid PHP code, inside the file:info.php

When you are finished, save and close the file.

Now you can test whether your web server is able to correctly display content generated by this PHP script. To try this out, visit this page in your web browser. You’ll need your server’s public IP address again.

The address you will want to visit is:

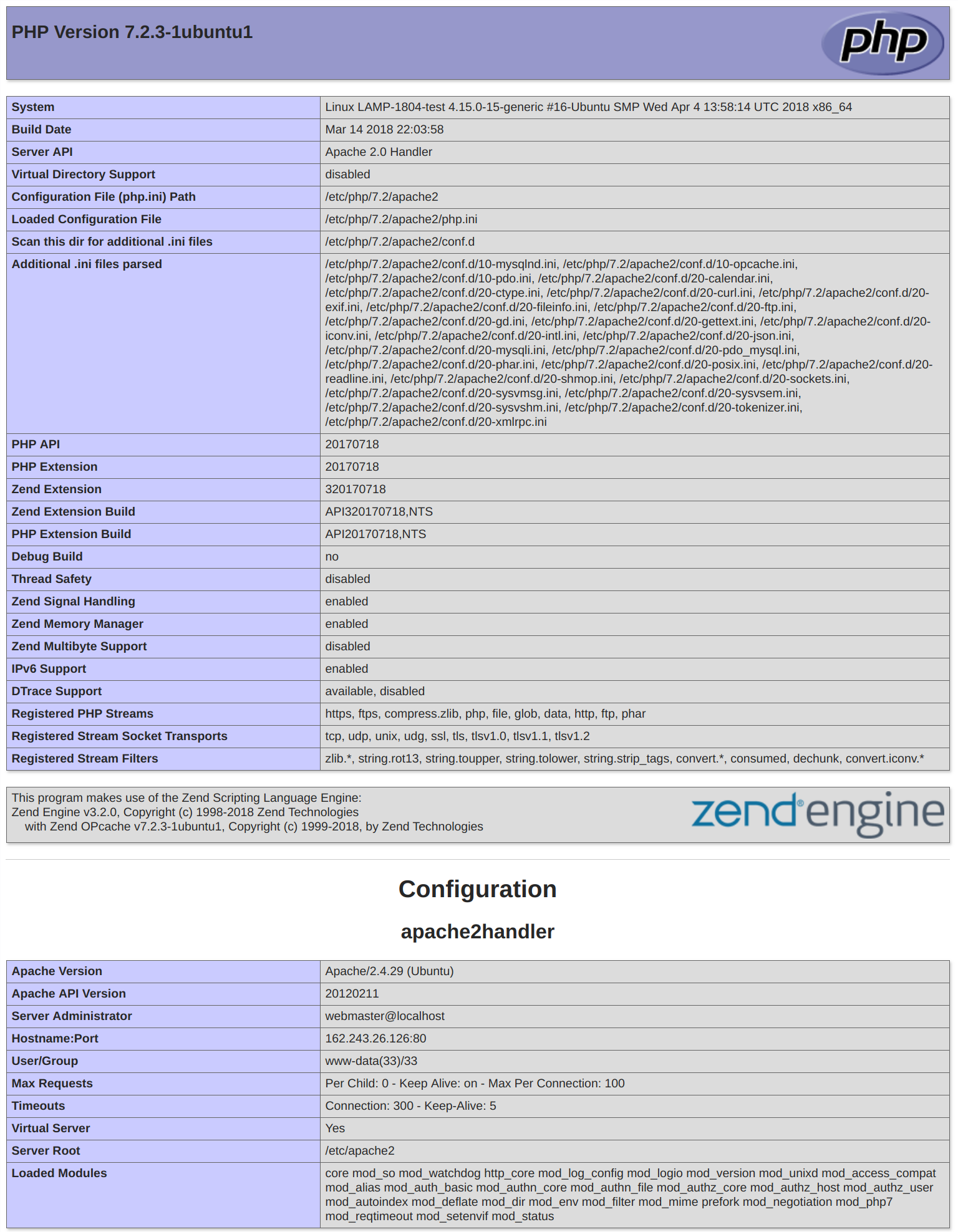

The page that you come to should look something like this:

This page provides some basic information about your server from the perspective of PHP. It is useful for debugging and to ensure that your settings are being applied correctly.

If you can see this page in your browser, then your PHP is working as expected.

You probably want to remove this file after this test because it could actually give information about your server to unauthorized users. To do this, run the following command:

You can always recreate this page if you need to access the information again later.

Conclusion

Now that you have a LAMP stack installed, you have many choices for what to do next. Basically, you’ve installed a platform that will allow you to install most kinds of websites and web software on your server.

Last updated